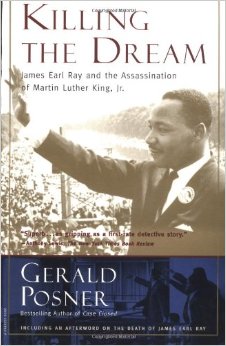

'Killing the Dream: James Earl Ray and the Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.'

by Gerald Posner

Random House, $25

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated by lone gunman James Earl Ray in Memphis, Tenn., on April 4, 1968, as King leaned over the balcony of the Lorraine Motel and joked with his staff. The CIA was not involved, nor the FBI, nor any other government agency. Just Ray - and maybe his deranged family - motivated by a $50,000 bounty said to have been posted for the killing.

So says investigative journalist Gerald Posner in his definitive study of the King assassination, "Killing the Dream." Posner, whose 1993 book, "Case Closed," demolished conspiracy theories surrounding the murder of John F. Kennedy, now takes aim at that other '60s-era assassination that remains shrouded in innuendo.

"Killing the Dream" sparks immediate interest from its opening account of the last days of the famed civil-rights leader and his involvement in labor turmoil in Memphis. Cutting back and forth between King and his lieutenants and Ray in his sniper's nest, Posner accumulates evidence of the assassination, of Ray's escape to Europe and his final capture by an alert customs agent at London's Heathrow Airport.

Making of a racist

Posner also details Ray's sorry life and sordid criminal history. Born into crushing poverty, he was initiated into a life of crime and alcoholism by his father and his career-criminal brothers. Ray absorbed his lessons well, committing numerous armed robberies, earning several prison sentences and developing a prodigious ability for creative alibis. In this environment, Ray's vicious racism took root early and flourished.

In the 30 years since King's assassination, conspiracy theories have abounded: that there was a covert team of military snipers in Memphis; that the FBI or CIA were involved; even that the supposed "grassy knoll" gunman from Dallas also killed King.

It is an odd, perhaps uniquely grotesque, feature of American popular culture that King's assassination, like JFK's, fostered this cult. Perhaps it is too awful to contemplate that men so powerful and inspiring could be silenced by just one lunatic. Life cannot be this fickle; a dream cannot be so easily stilled.

Posner persuasively demonstrates that Ray, who died April 23 still maintaining his innocence, killed King. He reveals, for example, Ray's marksmanship training in the military (overlooked by those who claim he couldn't have made the 207-foot shot), and that the trees near the Lorraine Motel were not cut down until two months after the assassination (not before, to give the assassin a clear view, as conspiracy buffs contend). Most convincingly, he cites innumerable inconsistencies in Ray's own shifting explanations.

Holes in the theories

After confessing to the crime, Ray later claimed he was an innocent dupe led into the crime by a mysterious man named "Raoul." By any reasonable measure, the story cannot withstand scrutiny. Why would a sophisticated conspiracy use Ray rather than a skilled hit man? Why risk having him run drugs to Mexico before the murder, as Ray claimed? And why allow Ray to live and threaten disclosure after the deed was done?

The most poignant part of "Killing the Dream" recounts the King family's belief that some larger conspiracy, even including President Lyndon Johnson, had a part in the killing. It is not difficult to sympathize with their loss - King certainly was subjected to FBI surveillance and outrageous efforts to undermine him - but it takes an unreasonable leap of faith to conclude that he was murdered by any government agency.

Overlooking the compelling evidence of Ray's responsibility does not advance King's legacy. Posner's careful analysis overpowers the various flawed and unsupported theories offered over the years. He pronounces this case closed - and his readers likely will, too.